The Triumph Factory

One of a series of photos taken by Howard Grey of the Triumph Production line in 1966, showing the testers standing between a row of Tiger 100’s and 3TA’s.

These rare images along with many other period shots can be viewed and purchased through Howard’s site at www.howardgrey.com, he has very kindly given me permission to use this fabulous image, I am hoping to identify the machines pictured.

Featured from Left to Right; Bert Watmore, Pete West, Jock Copeland and Steve Spencer, note the Barbour Jackets. Tucked under the Tank Racks are the Test Sheets that the Testers filled in to indicate problems with each machine if there were any. There is a Triumph advertisement from May 1966 that uses a similar image.

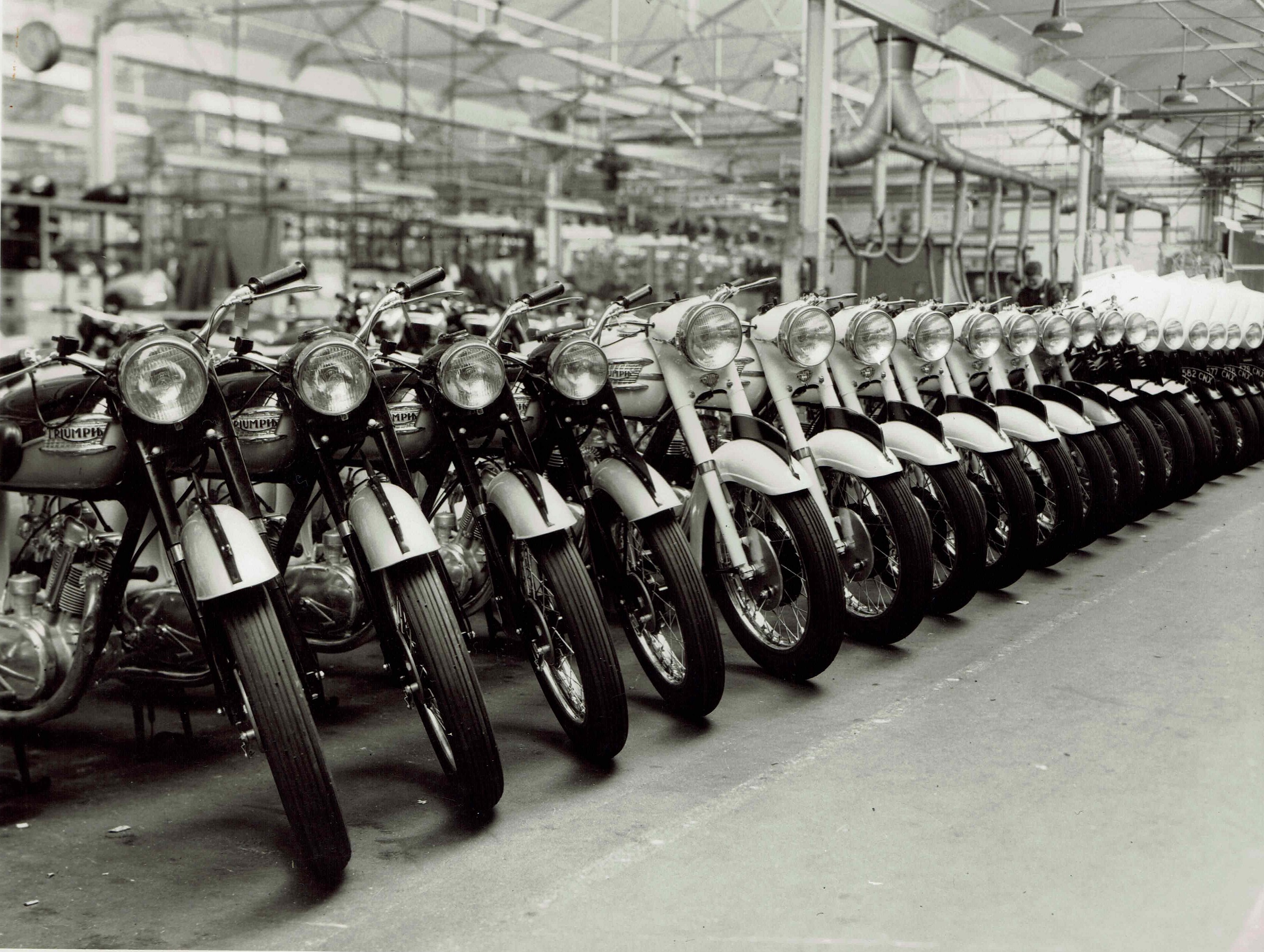

If you look closely at this photograph you will note the differing specifications, in the background are a number of 3TA’s finished entirely in white, while the 3TA on the right does not show a coloured stripe on the front mudguard or a number plate (for export).

On the Still Time Archive photos www.stilltimecollection.co.uk there are a number of images featuring Triumphs taken both at the old Priory Street factory and at the later Meriden Factory, with experience you can identify the locations.

Following the destruction of Triumph’s factory in Coventry on the night of the 14th November 1940 a new site was selected on land owned by Jack Sangster between Coventry and Birmingham near the village of Meriden …..

Between March 1957 and 1973 Triumph at Meriden produced some 100,000 ‘C’ range machines along with the numerous other Machines in the Triumph range. I have been fortunate to interview John Nelson who wrote the following article.

I am always amazed by the vast range of questions that are asked regarding the production of motorcycles from the original factory in Meriden. Most can only be answered from the ‘incomplete’ records made at the time, and the memories of the dwindling few that worked there, and still exist (and retain their memories)!

My first statement is that there was no one at the factory who was detailed to study and record each individual machine and function so that he could recall precisely sixty years later. What records that were kept were for business and legal purposes.

Secondly, Triumph was not just a motorcycle assembly shop from bought in finished components as were many other makes. When I joined in nineteen fifty, they made their own pistons, frames, gears, shafts, clutches, wheel hubs-polished and plated their wheel rims, handlebars, silencers in modern paint, polishing and plating shops. The machine shops manufactured almost every part for engines and gearboxes, and all was subject to very strict inspection and quality procedures.

So! How did it all work? In the nineteen fifties and sixties, Edward Turner was in charge. Each year he approved design changes, and new models down to every nut and bolt. Most proposed changes were submitted by Sales for acceptance following market trends and Distributor and Dealer requests. Once agreed, the new seasons models were specified by the Design Department, and a specification issued for each model, by part number detailing quantity, material, etc. indicating ‘new’ where appropriate. When these were issued, Sales issued a programme of forthcoming sales requirements which went to the Purchase and Production departments. Purchase had to schedule deliveries of raw materials to cover manufacturing requirements in time for Production to commence at the proposed date. Tallies were issued to each section in the factory detailing quantities for each individual component in scheduled batches for delivery in time for inspection, and transfer to the central ‘finished ‘ stores. The finished stores was in a central position in the assembly area, midway between the engine and gearbox assembly tracks, and the motorcycle final assembly line.

By this time, the Sales departments (Home and Export) had collected the forward orders for the forthcoming season, and converted these into coloured cardboard Tallies (White for Home and General Export, and Pink for Overseas Markets), detailing individual model, destination, Distributor or Dealer, additions to specification, packing and despatch etc. All these Tallies were collected in single model and destination batches and passed down to Production and Planning to be attached to the bare assembled frames, forks and wheels and handlebars, as the machine was placed on the final assembly track. By this time the Engine Assembly track, on the other side of the finished stores, was commencing build of the new seasons specification engines. Nothing had a frame or engine number at this point. As the engine ‘grew’, and after the pistons and barrels had been fitted, the designated operator sequentially stamped each individual letter and number on the crankcase, whilst standing by the engine at waist height, (not easy!) and then recorded it in the build book. Passed on to the next operators, the engine was then completed, collected in a batch at the end of the track, and then shipped in batches round to the final assembly track, and fitted into the next frame going down the line. The engines were picked from the engine bench supply in random order and it was not until the last operation on the finished motorcycle, just before it was passed down to the testers that the frame number (taken from the engine number) was stamped by hand, using individual stamps on the headlug -(later an adhesive label), and the number entered on the Tally, and then into the build register. On rare occasions, due to frame hold-ups, large stocks of engines gathered awaiting build, and no attempt was made to ensure they were segregated and then fitted in chronological order. An engine was a bike; which was an invoice, and an income.

When passed test, (or rectification, and then re-test) the machines were delivered to the Despatch department, stripped as required for shipment, packed, crated – or delivered by truck, as specified. A dispatch record of every machine was also logged by the despatch department, the completed Tallies were then returned to the Sales departments, and the final records completed….and the invoices dispatched. During every stage of the above procedures, there were a large complement of progress chasers, based in the production department whose sole job was to ensure the material from the ‘rough stores’ was presented to the various machining sections in time for each batch manufacture, heat treatment, plating/polishing in accordance with the schedule, and available in time in the central stores for each day’s supply to the tracks in accordance with the day’s model build programme, (and as you will appreciate, the constant supply of finished material for the Spares Department).. Everyone knew the programme, and what they were building, normally starting with 650 6T’s TR6, T110, and T120, in those days, and eventually 750’s TR7 and T140’s. In the early days 350/500’s and Police and military were usually at the end of the sequence. Then it was all round again and no going back to earlier models.

New models were usually introduced immediately following the Annual Works Holiday, when a skeleton staff had been retained to install the new jigs and fixtures to be used for subsequent production, and a number of dummy runs made to solidify any new installation procedures required for the return and start-up when the operators returned- so all was ready to go! This was the time when the routine changed to supply the U.S. with early consignments of the new models, so they could be shipped and distributed and displayed across the USA in time for the spring selling season. Imagine what happened when the new frame from Umberslade was introduced three months late, and then the engine couldn’t be installed. The entire selling season was lost, and the decline set in.

The records that I have show factory deliveries to Tricor and Jomo between the years 1958 and 1965.

| Year | Production | Tri-Cor | T120 | Income £ | Jomo | T120 | Income £ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1958 | 23633 | 2797 | 300 | 458333 | 1756 | 195 | 260920 |

| 1959 | 26532 | 3267 | 849 | 491816 | 2458 | 487 | 345309 |

| 1960 | 28859 | 3799 | 882 | 600672 | 2787 | 671 | 438949 |

| 1961 | 27914 | 1478 | 391 | 232917 | 1009 | 135 | 152999 |

| 1962 | 16083 | 2460 | 772 | 410214 | 2047 | 560 | 333361 |

| 1963 | 14718 | 4295 | 1519 | 738914 | 3378 | 1206 | 584303 |

| 1964 | 16348 | 4802 | 2593 | 909013 | 4773 | 1779 | 859673 |

| 1965 | 16658 | 8807 | 4727 | 1888692 | 6531 | 2820 | 1324803 |

T120 figures are included within the overall totals. ‘Income’ figures are factory invoice value.

‘Production’ is the total Meriden output figures for the periods shown.

Another important feature about the U.S Market, when investigating U.S. models, is that both Distributors were there to sell the machines. They offered Dealer update parts to shift the products, altered machines within their own warehouses, sold them as models the factory had never heard of. The competition between the two main distributors was who could clear last year’s stock the soonest. so don’t ask me about anything that turns up there after fifty years or more. Whatever it is, it left the production line to spec!

John Nelson August 2011.

Completed Police Machines of various models lined up in preparation for Packing and Dispatch.

As John indicates, Production is in batches of similar machines, Please note the vast majority of machines were for export, and were produced to special order for police, government and military duties and reading the despatch books is an education in manufacturing for export. These machines were often made to differing specifications than standard, very few pictures survive and even fewer machines survive in original condition.

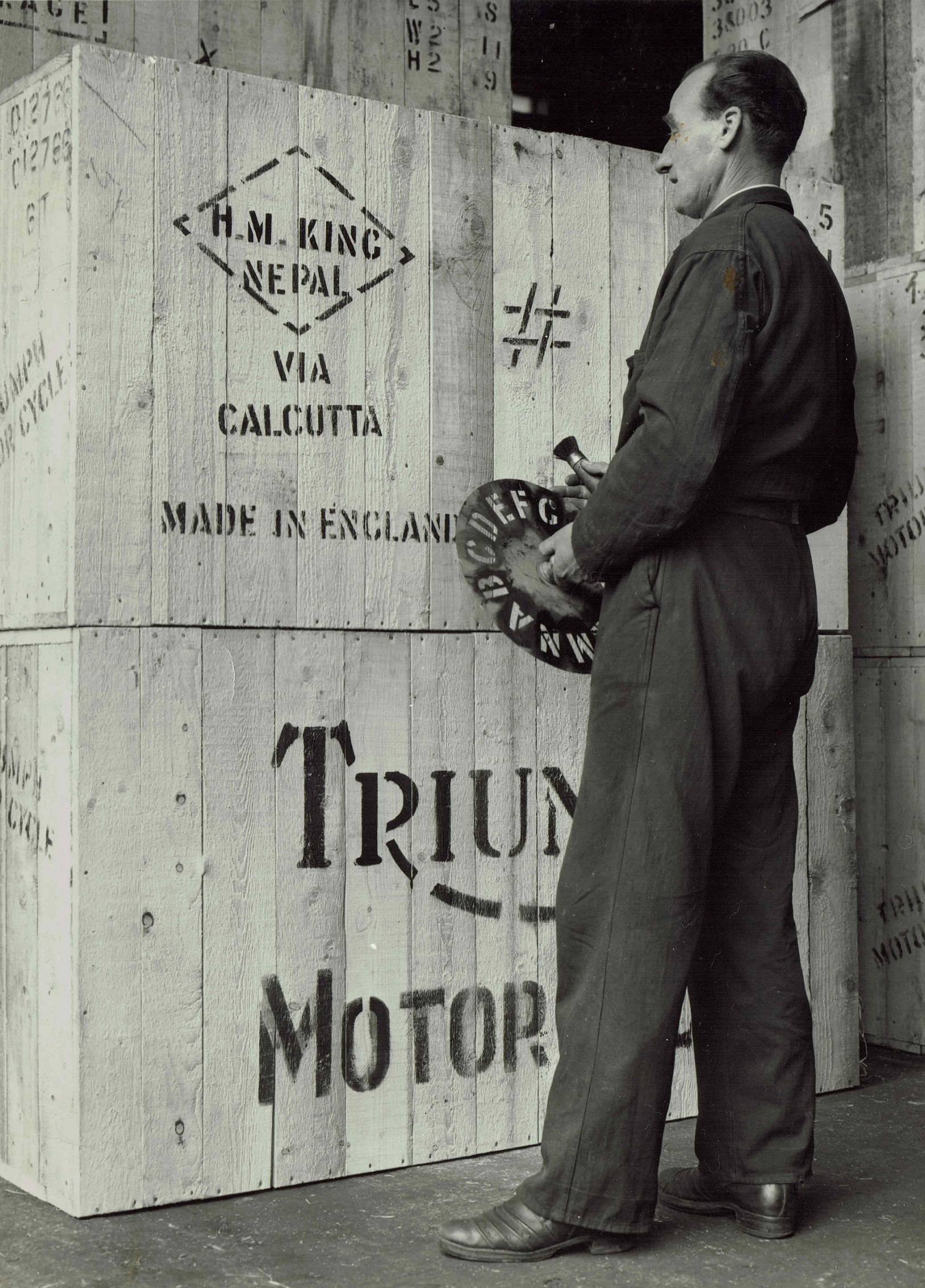

Once machines had passed final testing they were taken to the packing department, partially dismantled or in some cases fully dismantled (CKD usually Ireland) and then carefully packed in purpose designed Cases.

The Packing Cases used by Triumph were supplied by G.B Developments of Kenilworth, machines would have the handlebars, footrests and front wheel removed and the machine would then be secured into the Crate, machines for the UK would generally not be packed but transported complete.

Machines for Ireland were supplied completely dismantled (CKD) to evade import duties on complete vehicles.

Shipping time for the USA was 14 Days to Tri-Cor and 21 Days to Johnson Motors.

A delivery to Nepal, you can just make out the machine details on the side of the crate !

Home Market machines do at least seem to be standardised, these are ordered by motorcycle dealers as potential sales. The Triumph brochure would have been printed to coincide with production for the coming year in order to stimulate public interest. There are some home market machines made to special order, for Factory publicity, Police or MOD duties. And these will have differing finish and fittings over standard.

My work transcribing the records continues and interestingly more Tiger 90’s are produced than home market Tiger 100’s

I have in the records come across one single surviving order sheet for a batch of 3TA’s

This shows these machines made in small sub batches before a change is made to fulfil a particular requirement, i.e. Colour or Electrical arrangement. So though the written record shows some 135 3TA’s made in this period; only this sheet details the differences applied, this makes identifying the exact specification of any machine a potential nightmare because as far as I am aware no other order sheets form this period survive. I would like to know what colours and specifications the Tiger 90’s for the Ministry Of Supply in Ghana were, what was the specification of Burmese Police machines, was the 3TA sent to the King of Nepal special in any way! Actually one survives from the Nepalese Embassy now under restoration in Finland.

Furthest flung Triumph so far is a Tiger 90 that went to St Helena and I have a correspondent in the Cook Islands with a collection of 3TA’s, look it up on the map!

Production for each model year usually ends in July the Factory then went on Holiday. Production would often recommence with special machines for show duties or export. Required daily production by 1965 was 60 machines but this figure increases gradually to 1968 when it peaks at 140 machines (one every few minutes)!

Below is an essay by Chris Hemming (Labour Party History.org) that I have edited and included for its historical value.

The new company was owned by Manganese Bronze Holdings (MBH) controlled by Dennis Poore with the State as a major stakeholder.

NVT immediately proposed to rationalise the business from three factories to two by closing the Triumph Meriden factory with the loss of 1,750 jobs.

The Triumph workers reacted unremarkably for the time in response to redundancy by occupying the factory for the next eighteen months.

At the end of the occupation the remaining 200 workers at Meriden resumed work for a company that they controlled and with the financial backing of the Labour government.

Unfortunately as Meriden reopened the government was embarking on a new course, Eric Varley replaced Tony Benn the pro-state interventionist Industry Minister and the Treasury increased its control.

During 1973-75 the motorcycle operations of NVT slipped into liquidation leaving Meriden the sole surviving British motorcycle manufacturer. Management Today commented that ‘There can be few cases of industries collapsing so swiftly and so completely.’ This study concentrates on the weak performance of the industry during its final period. However, it acknowledges the Steve Koerner thesis that the underlying factor responsible for the decline was the inter-war strategy to concentrate on low volume production of larger machines generating higher profits.

The history of the British motorcycle industry is one of gradual and irregular decline from global supremacy in the 1930s.

There are a small number of studies of the industry but not as proliferate as that for the British motor vehicle Industry. BSA, as a company has some similarity to Leslie Hannah’s description of corporate development in Britain in Rise of the Corporate Economy. It grew from an armaments manufacturer to an industrial holding company absorbing several legendary motorcycle names to become the dominant British manufacturer.

BSA displayed the common weaknesses of a holding company as described by Derek Channon in The strategy and structure of British enterprise, it lacked a central policy making direction and the Board strategy was in essence to have no strategy. One cause given by Management Today was that ‘British firms were small and run by men with limited management horizons.’ BSA had nothing approaching a complex managerial hierarchy that Alfred Chandler described in Visible Hand or Strategy and Structure.

Even after the management consultants McKinsey had recommended a move to a multi-divisional form in 1964, its introduction was very problematic and caused conflict between existing management.

Edward Turner reacted to the introduction of the multi-divisional form by declining to take an interest in the BSA and Ariel factories in Birmingham, rarely leaving Meriden. Meanwhile the whole company became ossified with ‘BSA and Triumph…fighting each other almost to the bitter end.’

Ironically, it was Turner who had identified the smooth multi-divisional structure at Honda of Japan on a visit in 1960.

Honda shared with BSA both a foundry and a machine tools division but unlike BSA with its separate firms, the divisions at Honda were fully integrated into the structure. The BSA Company attempted to integrate its motorcycle operations, and although transaction costs were reduced the results illustrated by a former BSA Executive, Bert Hopwood were almost absurd.

The decline of industrial Britain often referred to as the ‘British disease’ has been a common feature of academic research since the 1970s. The primary reasons have been given as low productivity and a declining rate of profit together with the gradual loss of both home and export markets.

Although much research has been done on the motor vehicle industry there have been minimal published scholarly studies of the motorcycle industry.

The British motorcycle industry of the time shared a number of similarities with British car industry, such as problems associated with a wide product-range, labour intensive production, weak management and declining profitability. The motorcycle industry is however distinguished by its far higher rate of decline from being the third highest export earner in the 1950s to virtual collapse by the mid 1970s.

Despite the rapidity of decline of the motorcycle industry, institutional studies of the motor vehicle industry bare some similarity in respect of the relationship between government, industry and workers. The industry blamed the decline on Japanese competition, caused by government policy that had forced them to neglect the home market because of ‘fiscal measures’ and interference. The only defence of the industry is a reply to this debate by the right-wing Conservative ‘think-tank’ Centre for Policy Studies that government intervention can be blamed for its disappearance.

However the only comprehensive business history of the industry by Steve Koerner argues that it collapsed because of ‘internal weaknesses’. The study suggests that there was no single factor but several contained in three phases. The factors ranged from the ineffective response to the collapse of demand during the 1930s, failure to develop a cheap lightweight product during the post-war boom, to the final phase when managerial ‘culture’ misguidedly dismissed Japanese competition.

At the 1969 BSA Annual Meeting, the Chairman agreed that Japanese competition was beginning to encroach into the ‘super-bike’ segment of the USA market.

Unfortunately, as another BSA executive admitted, their response was to do nothing. The failure of the industry to meet the challenge from Japan was one of the chief criticisms of the 1975 Boston Consulting Group report commissioned by Tony Benn. The past performance of manufacturers was heavily criticised, they had been too preoccupied with ‘short-term profitability’ at the expense of long term competition. The report outlined the weaknesses of the British plants that ‘show all the signs of many years of chronic under-investment…the factories have effectively no experience of high volume, low cost, highly automated manufacturing and assembly methods.’

According to Doug Hele the former Chief Designer at Triumph to get more production they employed a larger workforce ‘rather than investing in more sophisticated machine tools. The money at the time should have been ploughed into tooling for the more modern motorcycles, realising as they did not, that it would take five years to develop a modern motorcycle.’

The Boston Group criticised the ‘segment retreat strategies’ of the industry ‘in the long run…they are almost always disastrous.’ This has been challenged by Karel Williams et.al. for ‘placing too much emphasis on the difference between British and Japanese market philosophies.’ They argue that the strategy adopted by the industry to retreat and concentrate on ‘superbikes’ was logical because conditions in Britain ‘enforced short-run objectives.’ The retreat to the ‘superbike’ market was probably the only option open to the industry although domestic demand was sluggish the North American market was expected to grow. Martin Fairclough contests the view that the industry had a segment retreat strategy, the much larger small lightweight market had only been abandoned after an attempt to develop new products had failed and aggravated the problems.

The third sector as Table 1 shows, the 250cc to 500cc category, was rapidly shrinking and identified by Barbara Smith as one of the causes for the industry’s decline.

| 1958 | 1972 | |

|---|---|---|

| Up to 250cc | 977000 | 874000 |

| 250cc - 500cc | 286000 | 47000 |

| 500cc and above | 54000 | 59000 |

For Dennis Poore the future lay in ‘an explosive technological effort to catch up with the Japanese’ the problem was that resources to commence such a project were beyond the capacity of an ailing industry.

In the early 1970s output was 50,000 motorcycles or fifteen per man year. In comparison, the capital intensive methods of Honda, Yamaha and Suzuki each made between one and two million machines with output per man year varying between 100 to 200 motorcycles.

British workers used multi-purpose machines sixty per cent of which were over twenty years old and some were quite ‘vintage’.

Once the Co-operative had started production assembly was still ‘controlled by hand and not machine’ but output increased from twenty one to twenty six motorcycles per man year. Organisational reforms included the end of demarcation between jobs, an egalitarian wages system and the sharing of knowledge. The outcome was a staggering fifty per cent increase in output despite the transfer of some of the more modern machinery to NVT.

Robert Oakshott has suggested that the productivity increases recorded could provide the solution to the productivity gap attributed to poor labour relations by Pratten in his international comparative study.

The Secretary of State for Industry in 1975, Eric Varley, told the House of Commons that the major problem with the motorcycle industry had been ‘the great failure of British management in the industry over the years.’ The failure of management, one of the principle criticisms of the Boston Report is echoed by Williams et.al. who argue that firms did not have the ‘managerial resources to take on Japanese mass producers’ that ‘controls [were] primitive or non-existent’ and the motorcycles were not ‘cost-engineered

at design stage’.

Martin Fairclough endorses this argument, the small team at Triumph were ‘recruited for motorcycle expertise and enthusiasm…rather than general management skills.’ The NVT Chairman claimed that one of the reasons Meriden was to close was because of poor management who had not the competence to organise the flow of supplies

to the factory.

Robert Oakeshott has suggested that workers resented having to pay for poor management with their jobs and consequently were keen to support self-management. The legacy continued after the birth of the co-operative, conventional management was considered unnecessary.

At Meriden opinion about workers management competence was ignored and all positions were elected from the shop floor except for a handful of specialist professional managers. However, by 1977, technical and financial factors forced a reappraisal of management positions and Meriden became the subject of voluntary expertise until Geoffrey Robinson became Chief Executive in 1978.

One of the factors identified by Williams et.al. as being responsible for Britain’s poor performance at manufacturing was employers control over the labour process and their difficulties in dealing with a heavily unionised workforce. At Meriden, the workforce was fully unionised but unlike plants in the multi-union motor industry eighty per cent of the workers were in one trade union. Labour relations were relatively harmonious more akin to the atmosphere of a ‘family’ firm and most issues were resolved over a ‘packet of Woodbines.’ Management control over the shopfloor was delegated to experienced craft workers who were invariably the fathers of sons or daughters working at the plant. Labour market conditions in the Coventry area by the 1970s were such that the firm increasingly had to rely upon external recruitment rather than family connection, the ‘new comers were ejected unionists from the car plants.’

In 1972, Meriden workers were the highest earning engineering workers in Britain. Something, which Bert Hopwood attributed to a strong union with ‘expert’ negotiators over piece rate bargaining, high product demand and a management team concerned with ‘production at any cost.’ The delegation of management control, once

of mutual benefit, now resulted in over-capacity and over-manning as sales declined.

The final two years of BSA control over Meriden were categorised by widespread strikes as management attempted to retrieve control thus adding to the poor performance of the company and an eleven per cent drop in production for the 1972-73 year.

Hopwood had an affinity for the Meriden workforce and was disappointed in their response to revitalise the company and its products in 1971.

Despite being let down he believed that the workers at Meriden would support the plans of management once explained sympathetically.

These two years were crucial for the firm’s survival. Despite the research indicating their affinity with Triumph it may well be true as Alan Fox has argued that workers do not see themselves tied to the success or failure of the enterprise in which they work. This is contradicted by a Times report that substantiates the view that Triumph workers were not only proud of their motorcycles but had a long-term stake in the company. Workers in response to a question ‘how long have you been here?’ told the journalist ‘I’m a newcomer, I’ve only been here eight, nine, ten years. Most told me over twenty, thirty or even forty.’

Although Triumph was part of the industrial scene in Coventry the low labour turnover was in marked contrast to the high turnover experienced in the nearby car plants.

One of the key features of Meriden was the preponderance of family groups working within the plant which had been fostered to meet the demands of the tight Coventry labour market during the 1950s and 1960s.

The motorcycle industry and the Meriden story are inextricably bound up with government and its transition from a hands off approach to an interventionist stance and then its reverse.

Until the 1970s, despite being a major dollar export earner, it was never considered an important component of Britain’s manufacturing structure.

Only when BSA was on the verge of collapse in 1973 did the Conservative government intervene. In a controversial move the government brokered the NVT deal with the injection of £4.8 million for shares in the new company and MBH purchased all the non-motorcycle assets of BSA for £3.5 million.

One critic, Jock Bruce- Gardyne argued that this was purely a two year holding operation rather than a long term survival plan for the industry.

The Department of Industry, after the 1972 Industry Act, became more interventionist and the policy continued after Labour came to office in 1974 until 1979. However, government policy was applied inconsistently.

Under the direction of Tony Benn there was a twin track approach to the industry. The first was emphasised by Benn in terms of his overall objectives for greater public ownership including the motorcycle industry. The second was greater industrial democracy to which Benn was heavily committed and the workers at Meriden were the vanguard for this policy.

The phenomenon of the anti-redundancy co-operative was not unique to Britain but the sponsorship by the state was, and this is attributed to the determination of Tony Benn. When Eric Varley replaced Benn the policy reverted to the pre-1974 corporatist model of intervention. Yet the Treasury had consistently throughout applied a non-interventionist stance in the application of valuable ECGD export credits and was the instigator of the final collapse of NVT.

| Exports | Imports | |

|---|---|---|

| 1972 | 43877 | 49984 |

| 1973 | 41091 | 59585 |

The evidence would appear to suggest that Poore, despite his public statements supporting a revitalised industry, had no definitive plan to turnaround the business.

NVT argued that a two factory industry was the only alternative and chose Meriden as the one to close despite plans for increased output.

Before the collapse of BSA, a firm of consultants had recommended the closure of Small Heath a Victorian inner city factory considered ‘out of date’.

Dennis Poore denied that he was aware of the report and argued that expanded production at Small Heath was possible because it had additional space.

In contrast, the Meriden plant was the only purpose built motorcycle factory in Britain and was already working at undercapacity.

The shop stewards at Meriden believed that Poore had interests in property development and that it was designated for closure because it was valuable housing development land. (The Factory site is now a housing estate)!

The motorcycle industry ‘was beyond saving by 1974’ but the Meriden cooperative was ‘doomed from the date on which…it was so unthinkingly launched.’

This essay has reviewed some of the general literature surrounding the poor British manufacturing performance and concurs that only a vast effort beyond the political will or circumstances of the time could have rescued the motorcycle industry.

For the Meriden Co-operative the upheaval within the industry could not have happened at a worse time. Sales were totally dependent upon the North American market and due to the oil crisis of 1973, the market for motorcycles suddenly soared and manufacturers in particular increased production. By the middle of 1974 it became apparent that this was a ‘blip’, the US market had not increased but declined. Japanese manufacturers like Honda with a massive stockpile of machines, equivalent to one year’s production, reacted by slashing prices and increased their share of the US market.

The Meriden Co-operative continued trading until 1983. However, by 1979 the difficulties were of such magnitude that the Managing Director, Geoffrey Robinson MP had to advise the trade unions that redundancies were

inevitable.

Unlike the rosy picture painted by supporters of the Co-operative, Robinson was blunt in his description of the financial crisis that had been inherent from the beginning.

The first was the company gearing that made it ‘wholly unrealistic from the start…to service the government loan.’

The second was the control over marketing and sales but held by NVT until May 1977 when the Co-operative was able to buy the rights.

Finally, attempts to recover the North American market were dealt a blow due to the twenty one per cent revaluation of sterling.

‘Ever since it started up in business in March 1975 Meriden had been producing more bikes than it sold…furthermore the motorcycles had been sold at a loss.’

Chris Hemming Labour Party History.org

Initial marketing and sales in the US by the Japanese concentrated on small capacity machines, promoting them to a new ‘Non Motorcycling’ public as inexpensive transport and leisure machines. Once the Japanese products and brands had become known, increased capacity and technological advances were introduced.

All the Japanese manufacturers were rapidly developing their manufacturing plants, processes and designs, I have restored both Japanese and British machines from the same period and it is amazing to see the differences in technology. 1969 was a watershed year with the introduction of the revolutionary ‘Honda Four’ the rest is history ….

For more information on the Demise of the British Motorcycle History refer to both Bert Hopwood’s ‘Whatever Happened to the British Motorcycle Industry’ and

Steve Koerner’s book ‘The Strange Death of the British Motorcycle Industry’. Also look for Abe Amidor’s “Shooting Star” published in the USA in 2009

Another excellent book with details of life at the factory is Neale Shiltons ‘A Million Miles Ago’ by Haynes ISBN 0-85429-313-2

The Triumph Factory Records

American Visitors Anne and John Adden and Sue Mason Picking up their new Cubs.

The Triumph Factory records are held by the VMCC at their Library in Burton on Trent, a microfilm copy is held by the Triumph Owners Club and administered by Richard Wheadon. John Nelson also has an extensive archive of factory material including Technical Bulletins, Modification Records and Factory photographs.

The Surviving Triumph Factory records contain some 200 books covering the entire production period of Triumph Meriden from 1942 until approximately 1983.

Earlier archive material was lost in the Coventry Blitz when the old factory was destroyed.

The records are divided into Models, Engine Records, Production Records and Dispatch Books.

The Engine Record books show the engine and gearbox specification applied to each engine and also record the changes to specification applied to all subsequent machines at a particular number, the record is in pencil and not easy to decipher, though the notes in the back are fascinating and were definitely written on the production line at the time. The engine record goes into some detail as to the various gearbox ratios and alternator variations used during production. The corresponding machine build book is less through and only gives the model codes without detail, it is interesting then tracing the final destination of certain machines but certainly not as cut and dried as I thought. It has shown me how very difficult it is to identify the specification applied to particular machines, assuming that a machine sent to Eastern USA is to one specification is incorrect, I have identified many anomalies.

The Production records show the model of each machine made, its date of manufacture, and the order number it relates to and some of the options fitted. It is possible to identify machines made to the same order though these can be separated by several others Machines though recorded in sequential order would not have been completed as such and can be occasionally be separated by several days!

The dispatch books show the order number, invoice and destination of each machine.

Most machines are dispatched complete, Some (very few) machines were supplied completely dismantled and shown in the records as CKD (completely knocked down) this was to avoid local import duties on complete machines and to utilise local labour.

I am researching the method of dispatching machines and the shipping agents used. I believe shipping manifests may still exist. I have seen one photograph showing the Ellerman City Line, City of Coventry being loaded with Triumph Crates, these feature the queens award to Industry Badge which dates the picture to 1967 or 1968 but where were they bound!

From the records Tiger 90’s were not marketed in the USA, verified by the 1963 USA brochure, which does not show the model and only 36 of all years were supplied to Johnson Motors (California) none to Tri-Cor.

3TA’s and 5TA’s were sold in the USA but the numbers are actually quite low when you review the sales figures.

My research is continuing into the exported machines such as the TR5AC, their destinations and bewildering variations in specification !

I am aware of surviving ‘C’ Range machines in Spain, Tenerife, New Zealand, Guam, Canada, Pakistan, Singapore and also machines from Burma, Ghana and Taiwan now in the UK.